治療抵抗性うつ病の管理─第一選択

治療抵抗性うつ病は治療困難で,転帰不良となることが多く1-3,特にエビデンスに基づいたプロトコルに従っていない場合4はなおさらである。治療抵抗性うつ病は均質な疾患ではなく,その重症度には複雑なスペクトラムがあり,段階評価が可能である5。治療抵抗性うつ病の転帰は重症度分類と密接に関連している6。治療抵抗性の単極性うつ病と思われる場合でも,実際には双極性うつ病であることが少なからずあり7, 8,このような場合は標準的な抗うつ薬が奏効しないことが多い9, 10(Chapter 2の「双極性うつ病」の項を参照)。最近,治療抵抗性うつ病を「治療困難な」うつ病としてとらえようとする動きがあるが,これは,治療抵抗性という表現が,うつ病の治療は有効であるのが普通であり,したがって効果がみられないのはどこか異常であるとの意味を暗に含んでいるためである11。臨床医が回復の見込みをより現実的なレベルで考えるのではなく,さらに多くの薬剤をさらに複雑なレジメンで試すよう促されてしまうため,治療抵抗性うつ病を診断名として使用するのをやめることを提案する(同じく「治療困難な」うつ病とすることを提案している)研究もある12。

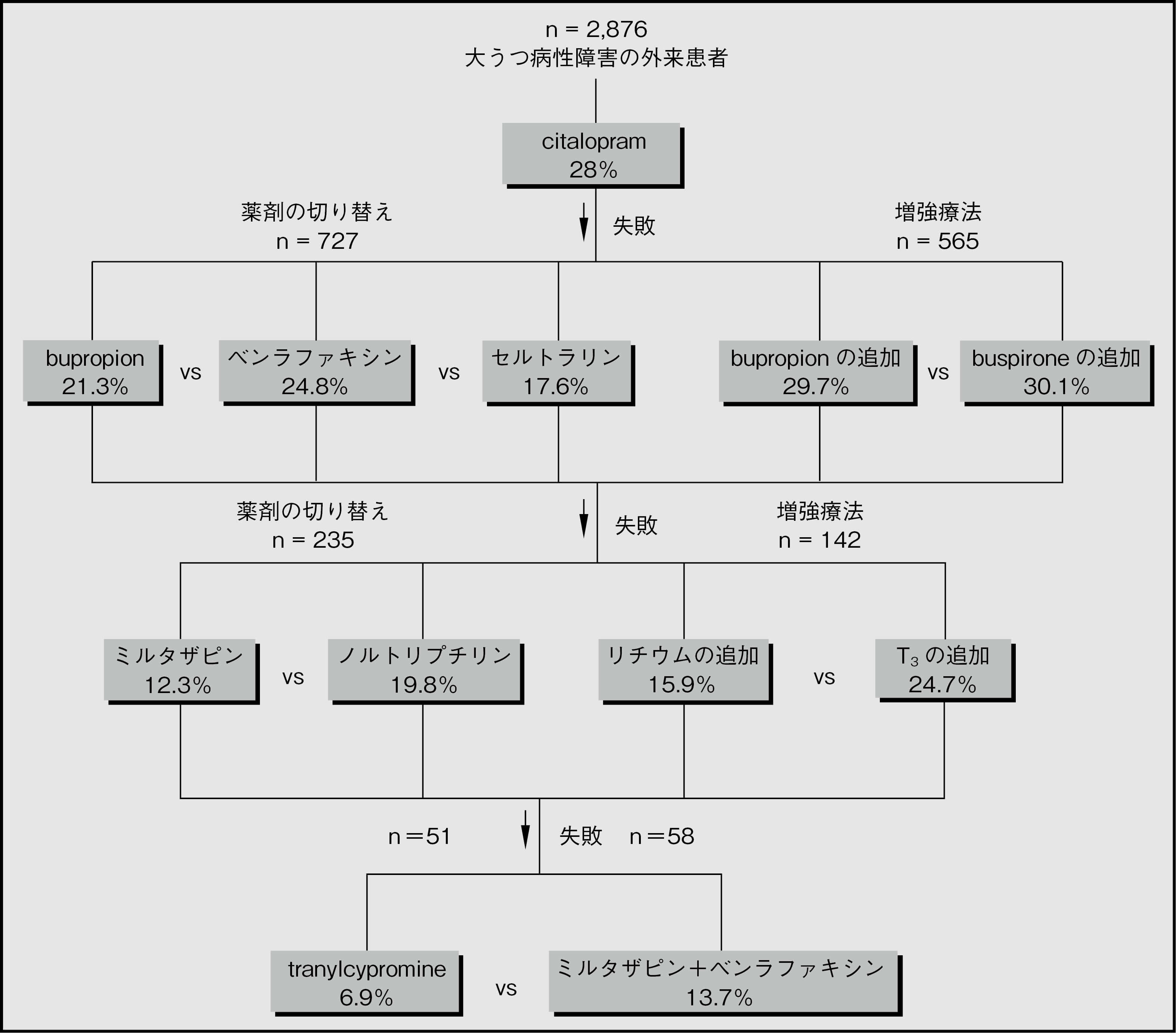

治療抵抗性うつ病の管理については,STAR*Dプログラム(Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression)から情報を得ることができる。STAR*Dは治療効果に関する実践的研究で,症状寛解を主要評価項目として用いている。ステージ113では,2,786例の被験者が14週間citalopramの投与を受け(平均投与量41.8mg/日),28%の被験者が寛解に達した[反応(症状スコアの50%減少)は47%であった]。寛解に至らなかった被験者は継続研究に登録され,次の段階の治療を受けた14-18。寛解率を図3.2に示す。この時点では,統計学的に有意な差はほとんど認められなかった。ステージ317では,T3はリチウムより忍容性が有意に優れていた。ステージ418では,tranylcypromineはミルタザピンとベンラファキシンの併用と比較すると効果も忍容性も乏しかった。図3.2にみられるように全体として寛解率は非常に低かったが,本研究の被験者は長期の反復性うつ病患者であったことに留意する必要がある。

図3.2 STAR*Dにおける寛解率

STAR*Dでは,治療抵抗性うつ病に対しては柔軟なアプローチが必要であり,特定の治療が奏効するか否かは薬理学的観点や以前の治療の結果から容易に推測できるものではないことが示された。このプログラムでは,bupropionとbuspironeによる増強療法を試みる価値のある治療選択肢として確立し,今まで曖昧であったT3による増強療法やノルトリプチリンの使用を復活させた。また,ミルタザピンとベンラファキシン併用の安全性と有効性(安全性ほど確実ではないが)もある程度確認された。

STAR*Dプログラムに対して妥当な批判が多数あることに留意する必要がある。批判されている点は,プラセボ群が設定されていないこと,治療および一部の評価が非盲検下で行われたこと,初回来院後に参加を中止した患者について理由が説明されていないこと,事前に規定された副次的評価指標が説明もなく主要な評価基準として用いられたこと,被験者に支払いが行われたこと,寛解が得られた1,518例の93%が12ヵ月の追跡調査期間に再発または研究から脱落したことなどである19, 20。これらの因子によって比較データの解釈が変わることはないかもしれないが,この研究で検討された抗うつ薬のレジメンで長期の治療抵抗性うつ病を治療しても効果があまり期待できないことがさらに強調されるのは確かである。

表3.3 治療抵抗性うつ病 - 第一選択:広く使用され,文献で概ねよく支持されている治療法(好ましい順ではない)

| 治療 | 長所 | 短所 |

| アリピプラゾール21-27(2-20mg/日)を抗うつ薬に追加 |

|

|

| リチウムを追加29 血漿中濃度の最初の目標は0.4-0.8mmol/Lで,十分な反応がみられない場合には1.0mmol/Lまで上げる |

|

|

| オランザピンとfluoxetineの併用31 (6.25-12.5mg+25-50mg/日,米国承認用量)* |

|

|

| クエチアピン35-40(150 mg/日または300mg/日)をSSRI/SNRIに追加 |

|

|

| SSRI+bupropion15, 41-45 400mg/日まで |

|

|

| SSRIまたはベンラファキシン +ミアンセリン(30mg/日)またはミルタザピン18, 45-48(30-45mg/日) |

|

|

*複合製剤を使用できない場合は,5mg+20mgから10mg+40mgが適切であると思われる。

eGFR:推算糸球体濾過量,NICE:英国国立医療技術評価機構,SNRI:セロトニン・ノルアドレナリン再取り込み阻害薬,SSRI:選択的セロトニン再取り込み阻害薬,STAR*D:Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression,TCA:三環系抗うつ薬,TFT:甲状腺機能検査

(桐野 創)

参照文献

- Dunner DL, et al. Prospective, long-term, multicenter study of the naturalistic outcomes of patients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:688-695.

- Wooderson SC, et al. Prospective evaluation of specialist inpatient treatment for refractory affective disorders. J Affect Disord 2011; 131:92-103.

- Fekadu A, et al. What happens to patients with treatment-resistant depression? A systematic review of medium to long term outcome studies. J Affect Disord 2009; 116:4-11.

- Trivedi MH, et al. Clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:669-680.

- Fekadu A, et al. A multidimensional tool to quantify treatment resistance in depression: the Maudsley staging method. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:177-184.

- Fekadu A, et al. The Maudsley Staging Method for treatment-resistant depression: prediction of longer-term outcome and persistence of symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:952-957.

- Angst J, et al. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:133-146.

- Smith DJ, et al. Unrecognised bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression. British J Psychiatry 2011; 199:49-56.

- Sidor MM, et al. Antidepressants for the acute treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2011; 72:156-167.

- Taylor DM, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of drug treatments for bipolar depression: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014; 130:452-469.

- Cosgrove L, et al. Reconceptualising treatment-resistant depression as difficult-to-treat depression. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8:11-13.

- Rush AJ, et al. Difficult-to-treat depression: a clinical and research roadmap for when remission is elusive. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2019; 53:109-118.

- Trivedi MH, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:28-40.

- Rush AJ, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1231-1242.

- Trivedi MH, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1243-1252.

- Fava M, et al. A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1161-1172.

- Nierenberg AA, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1519-1530.

- McGrath PJ, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1531-1541.

- Pigott HE, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants: current status of research. Psychother Psychosom 2010; 79:267-279.

- Pigott HE. The STAR*D trial: it is time to reexamine the clinical beliefs that guide the treatment of major depression. Can J Psychiatry 2015; 60:9-13.

- Marcus RN, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008; 28:156-165.

- Hellerstein DJ, et al. Aripiprazole as an adjunctive treatment for refractory unipolar depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2008; 32:744-750.

- Simon JS, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressants for the treatment of partially responding and nonresponding patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1216-1220.

- Papakostas GI, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1326-1330.

- Berman RM, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. CNS Spectr 2009; 14:197-206.

- Fava M, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aripiprazole adjunctive to antidepressant therapy among depressed outpatients with inadequate response to prior antidepressant therapy (ADAPT-A Study). PsychotherPsychosom 2012; 81:87-97.

- Jon DI, et al. Augmentation of aripiprazole for depressed patients with an inadequate response to antidepressant treatment: a 6-week prospective, open-label, multicenter study. Clin Neuropharmacol 2013; 36:157-161.

- Strawbridge R, et al. Augmentation therapies for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2019; 214:42-51.

- Undurraga J, et al. Lithium treatment for unipolar major depressive disorder: systematic review. J Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2019; 33:167-176.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults. Clinical Guidance [CG90]. 2009 (last reviewed Dec 2013); https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 .

- Luan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination in the treatment of treatment-resistant depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2017; 13:609-620.

- Takahashi H, et al. Augmentation with olanzapine in TCA-refractory depression with melancholic features: a consecutive case series. Human Psychopharmacology 2008; 23:217-220.

- Corya SA, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, olanzapine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine in treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety 2006; 23:364-372.

- Thase ME, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, olanzapine, and fluoxetine in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:224-236.

- Jensen NH, et al. N-desalkylquetiapine, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and partial 5-HT1A agonist, as a putative mediator of quetiapine’s antidepressant activity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008; 33:2303-2312.

- El-Khalili N, et al. Extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder (MDD) in patients with an inadequate response to ongoing antidepressant treatment: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010; 13:917-932.

- Bauer M, et al. Extended-release quetiapine as adjunct to an antidepressant in patients with major depressive disorder: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:540-549.

- Bauer M, et al. A pooled analysis of two randomised, placebo-controlled studies of extended release quetiapine fumarate adjunctive to antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2010; 127:19-30.

- Montgomery S, et al. P01-75 - Quetiapine XR or lithium combination with antidepressants in treatment resistant depression. Eur Psychiatry 2010; 25:296-296.

- Doree JP, et al. Quetiapine augmentation of treatment-resistant depression: a comparison with lithium. Curr Med Res Opin 2007; 23:333-341.

- Zisook S, et al. Use of bupropion in combination with serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:203-210.

- Fatemi SH, et al. Venlafaxine and bupropion combination therapy in a case of treatment-resistant depression. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33:701-703.

- Lam RW, et al. Citalopram and bupropion-SR: combining versus switching in patients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:337-340.

- Papakostas GI, et al. The combination of duloxetine and bupropion for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety 2006; 23:178-181.

- Henssler J, et al. Combining antidepressants in acute treatment of depression: a meta-analysis of 38 studies including 4511 patients. Can J Psychiatry 2016; 61:29-43.

- Carpenter LL, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augmentation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:183-188.

- Carpenter LL, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:45-49.

- Ferreri M, et al. Benefits from mianserin augmentation of fluoxetine in patients with major depression non-responders to fluoxetine alone. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 103:66-72.

- Kessler DS, et al. Mirtazapine added to SSRIs or SNRIs for treatment resistant depression in primary care: phase III randomised placebo controlled trial (MIR). BMJ 2018; 363:k4218.