抗うつ薬による再発予防

初回エピソード

うつ病の初回エピソードの場合は,完全寛解後少なくとも6-9ヵ月間は治療を継続する1。回復してすぐに抗うつ薬治療を中断してしまうと,50%の患者は3-6ヵ月以内に症状が再発する1。fluoxetineによる維持療法を評価した大規模試験1件では2,効果の得られている治療を12週間で中断すると再発に関する転帰が最も不良となり,続いて26週間で中断した場合,50週間で中断した場合に転帰不良となった(50週の時点ではプラセボと実薬とで再発率に差は認められなかった)。別の試験では,患者に「重大な症状が16-20週間みられない」場合にのみ中断を試みることを勧めている3。治療開始後6ヵ月間に抗うつ薬を断続的に使用した場合でも再発率が上昇する4。

反復性うつ病

大うつ病性障害は,症例の15%では寛解することがなく,35%では再発する。初回エピソードがあった患者の約半数は回復し,以降,エピソードが発症することはない5。うつ病の家族歴,反復性の気分変調症,気分障害以外の精神疾患の併存,女性であること,うつ病エピソードの期間が長いこと,治療抵抗性の程度6,慢性的な身体疾患,社会的要因(例:信頼できる人間関係がないこと,心理社会的ストレス因子)等の多くの要因が再発リスクを増加させる。処方薬のなかにはうつ病を引き起こすものがある6, 7。

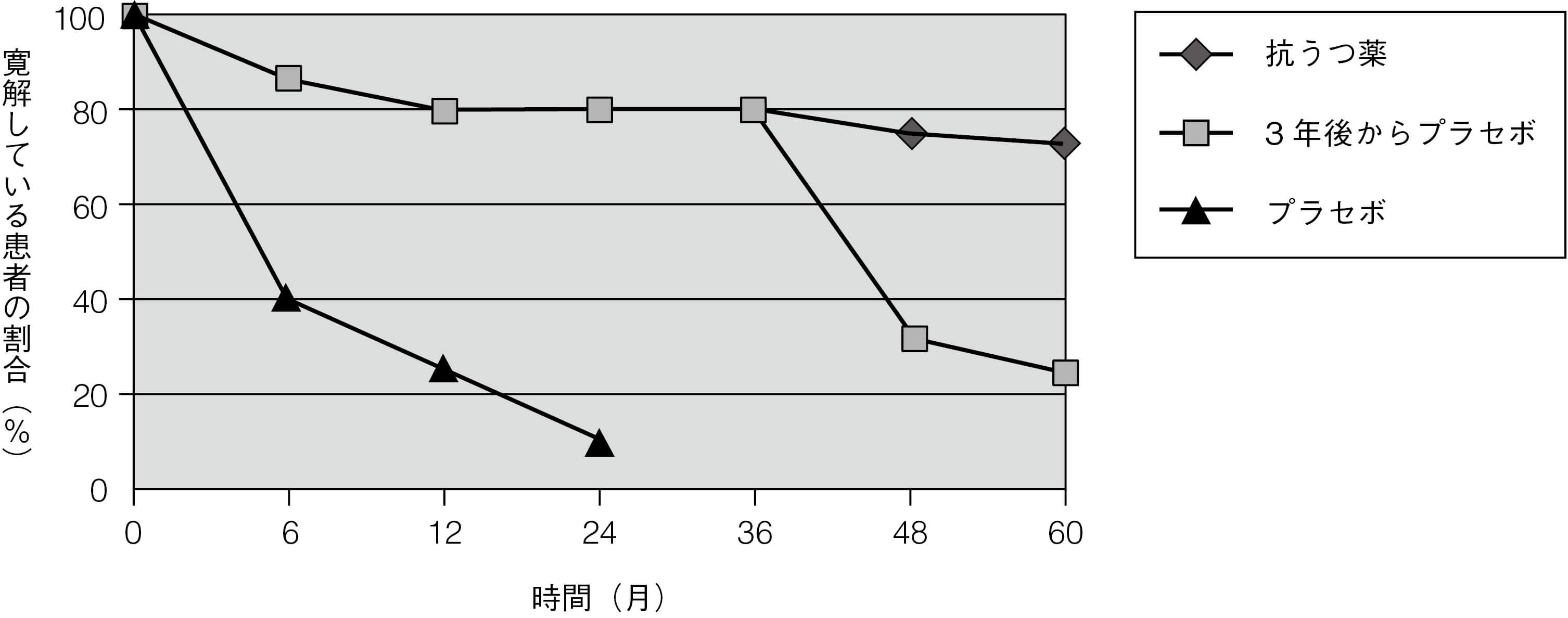

図3.5に複数のエピソードを有する患者の再発リスクを示す。この研究の対象は,3回以上のうつ病エピソードを経験し,エピソードとエピソードの間隔が3年以内の患者である8, 9。うつ病患者では心血管疾患のリスクが増加し10,自殺による死亡率も一般集団と比べて有意に増加する。

図3.5 複数のうつ病エピソードがある患者の再発リスク

3回以上のうつ病エピソードを経験し,エピソードとエピソードの間隔が3 年以内の患者を対象とした。

抗うつ薬を継続投与した研究のメタ解析によると11,抗うつ薬の継続投与によりうつ病が再発するオッズ比は約2/3減少し,これは絶対的なリスクを半減させることにほぼ等しい。54件の試験を対象とした最近のメタ解析でもほぼ同様の結果が得られ,再発のオッズ比は65%減少した12。再発リスクは治療中断後数ヵ月間が最も高く,中断前の治療期間には関係がない13。継続治療の有効性は36ヵ月以上持続し,様々な患者群(初回エピソード,複数のエピソード,および慢性)においても同様であると思われるが,初回エピソードの患者のみを対象とした研究はない。特に初回エピソードの患者を対象として6-9ヵ月以上治療を継続した場合の有益性を明らかにする研究が必要である。ほとんどのデータは成人のものである。

高齢者のうつ病における維持療法を評価した1件のRCTでは,対象患者の多くは初回エピソードで,抗うつ薬の継続は2年以上にわたって有益であり,効果量は成人と同様であった14。1件の小規模なRCT(n = 22)では,青年期の患者において再発予防のための抗うつ薬投与は有益であることが示されている15。

抗うつ薬による維持療法が有益かもしれない患者の多くが,実際には治療を受けていない16。最適な管理を長期的に行えば,うつ病による死亡率を大幅に下げることができる17。

一部の見解では,維持療法の試験では,交絡によって抗うつ薬の再発予防効果は過大評価されており,有効な薬物治療が突然中断された可能性があることから,再発リスクを高めているのは,(必ずしも中断したこと自体ではなく)このような中断の仕方であるとのことである18, 19。したがって,継続投与の方が優れているとの結果は,少なくとも部分的には,プラセボに切り替えた患者で最適ではない治療が行われたことによるものである。最近の試験では実薬治療の離脱期間がより長く(1ヵ月以上)設定されているが20,これでも離脱による負の影響を完全に排除するには十分でない可能性がある21。さらに,抗うつ薬は結局のところ治療の対象である病態を悪化させているのかもしれないとする少数意見もある22。この仮説は,以前に処方された抗うつ薬の数が多いほど,抗うつ薬に対する反応が低下するという観察によってある程度裏付けられる23。

他に抗うつ薬の長期投与で生じるおそれのある不利益は,消化管出血および脳出血のリスクの増加(本Chapterの「SSRIと出血」の項を参照),出血または低ナトリウム血症のリスクを高める薬剤を併用した場合の相互作用のリスク等である。

これらの観察結果は,維持療法の試験が主に寛解が得られている患者を対象に実施されたことも考え合わせると,抗うつ薬の投与は,実質的な有効性を示す明確なエビデンスがある場合にのみ継続すべきであることを強く示唆している。これは当然のことのように思われるかもしれないが,効果のない,あるいは部分的な効果しかない抗うつ薬の長期投与が一般に行われていることが臨床経験から示唆される。治療の目的は寛解の達成と維持とすべきである。残遺症状は,転帰不良および高い再発リスクの予測因子である24。

NICEの推奨を以下に示す25。

- 最近2回以上のうつ病エピソードがあった場合,およびこれらのエピソード中に著明な機能障害があった場合には,少なくとも2年間は抗うつ薬を継続することを提案すべきである。

- 維持療法を受けている患者については,年齢,併存疾患,その他の危険因子を考慮し,維持療法を2年以上継続する必要があるかどうかを再評価すべきである。

予防投与の用量

成人では急性期と同じ量を投与すべきである26。高齢者では,急性期よりも用量を減らした方がよいというエビデンスがいくつかある。ドスレピンを75mg/日で投与することは予防に有効であるが27,現在ではほとんど使用されておらず,専門医による使用に限るべきである。SSRIについては,標準量よりも減らすことを支持するエビデンスはない28。

ECT後の再発率は抗うつ薬を中断した後の再発率と同等である29。抗うつ薬による再発の予防では,理想的には最初に効果のなかった薬剤とは違う薬剤を必要とするであろうが,この分野に関する良好なデータはない。

リチウムも単極性うつ病の予防においてある程度の有効性が認められているが,抗うつ薬と比較した有効性は不明である30。しかし,リチウム治療は,単極性うつ病に対するどのような治療法のなかでも最良の転帰となることが示されている31。NICEでは,単極性うつ病の予防としてリチウムを単剤で使用すべきではないと推奨している25。リチウムとノルトリプチリンの併用については,いくらか支持するデータがある32。

リチウムによる維持療法は自殺を予防する26。

患者に知らせるべき重要事項

- うつ病の単回エピソードでは,寛解後6-9ヵ月間は治療を継続すべきである。

- うつ病の再発リスクは高く,エピソードの回数が増えると再発リスクは高くなる。

- 複数のエピソードがある場合には,数年にわたる治療が必要になるかもしれない。

- 抗うつ薬の服用を継続することで,良好な状態が維持される可能性が大幅に高くなる。

- 抗うつ薬には以下の特徴がある。

- 効果的である。

- 常習性はない(ただし離脱症状が出現する可能性がある)。

- 時間経過とともに効果が減弱するという知見はない。

- 長期間服用により新たな副作用が出現するという知見はない。

- 有効量の薬剤を継続することが必要である。忍容できない副作用が起きた場合でも,もっと適した他の薬剤がみつかるかもしれない。

- 患者が自分自身で薬剤を止めようと決めたとしても,急に中止してはならない。急に中止すると好ましくない離脱症状が出現する可能性があり(本Chapterの「抗うつ薬の離脱症状」の項を参照),再発リスクが高まる33。中止する際には,専門医の指導のもとで慎重に減量していく必要がある21。

(内田 裕之)

参照文献

- Cleare A, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacology 2015; 29:459-525.

- Reimherr FW, et al. Optimal length of continuation therapy in depression: a prospective assessment during long-term fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1247-1253.

- Prien RF, et al. Continuation drug therapy for major depressive episodes: how long should it be maintained? Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:18-23.

- Kim KH, et al. The effects of continuous antidepressant treatment during the first 6months on relapse or recurrence of depression. J Affect Disord 2011; 132:121-129.

- Eaton WW, et al. Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65:513-520.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management. Clinical Guidance [CG91]. 2009; http://www.nice.org.uk/CG91 .

- Patten SB, et al. Drug-induced depression. Psychother Psychosom 1997; 66:63-73.

- Frank E, et al. Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093-1099.

- Kupfer DJ, et al. Five-year outcome for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:769-773.

- Taylor D. Antidepressant drugs and cardiovascular pathology: a clinical overview of effectiveness and safety. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008; 118:434-442.

- Geddes JR, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 2003; 361:653-661.

- Glue P, et al. Meta-analysis of relapse prevention antidepressant trials in depressive disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010; 44:697-705.

- Keller MB, et al. The prevention of recurrent episodes of depression with venlafaxine for two years (PREVENT) study: outcomes from the 2-year and combined maintenance phases. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68:1246-1256.

- Reynolds CF, III, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1130-1138.

- Cheung A, et al. Maintenance study for adolescent depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2008; 18:389-394.

- Holma IA, et al. Maintenance pharmacotherapy for recurrent major depressive disorder: 5-year follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 193:163-164.

- Gallo JJ, et al. Long term effect of depression care management on mortality in older adults: follow-up of cluster randomized clinical trial in primary care. BMJ 2013; 346:f2570.

- Cohen D, et al. Withdrawal effects confounding in clinical trials: another sign of a needed paradigm shift in psychopharmacology research. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10:2045125320964097.

- Hengartner MP. Editorial: antidepressant prescriptions in children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11:600283.

- DeRubeis RJ, et al. Prevention of recurrence after recovery from a major depressive episode with antidepressant medication alone or in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy: phase 2 of a 2-phase randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2020; 77:237-245.

- Horowitz MA, et al. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6:538-546.

- Fava GA. May antidepressant drugs worsen the conditions they are supposed to treat? The clinical foundations of the oppositional model of tolerance. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10:2045125320970325.

- Amsterdam JD, et al. Prior antidepressant treatment trials may predict a greater risk of depressive relapse during antidepressant maintenance therapy. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2019; 39:344-350.

- Kennedy N, et al. Residual symptoms at remission from depression: impact on long-term outcome. J Affect Disord 2004; 80:135-144.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults. Clinical Guidance [CG90]; 2009 (last reviewed December 2013); https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 .

- Anderson IM, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacology 2008; 22:343-396.

- Old Age Depression Interest Group. How long should the elderly take antidepressants? A double-blind placebo-controlled study of continuation/prophylaxis therapy with dothiepin. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:175-182.

- Franchini L, et al. Dose-response efficacy of paroxetine in preventing depressive recurrences: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:229-232.

- Nobler MS, et al. Refractory depression and electroconvulsive therapy. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1994.

- Cipriani A, et al. Lithium versus antidepressants in the long-term treatment of unipolar affective disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; CD003492.

- Young AH. Lithium for long-term treatment of unipolar depression. Lancet Psychiatry 2017; 4:511-512.

- Sackeim HA, et al. Continuation pharmacotherapy in the prevention of relapse following electroconvulsive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285:1299-1307.

- Baldessarini RJ, et al. Illness risk following rapid versus gradual discontinuation of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167:934-941.