うつ病の薬物療法

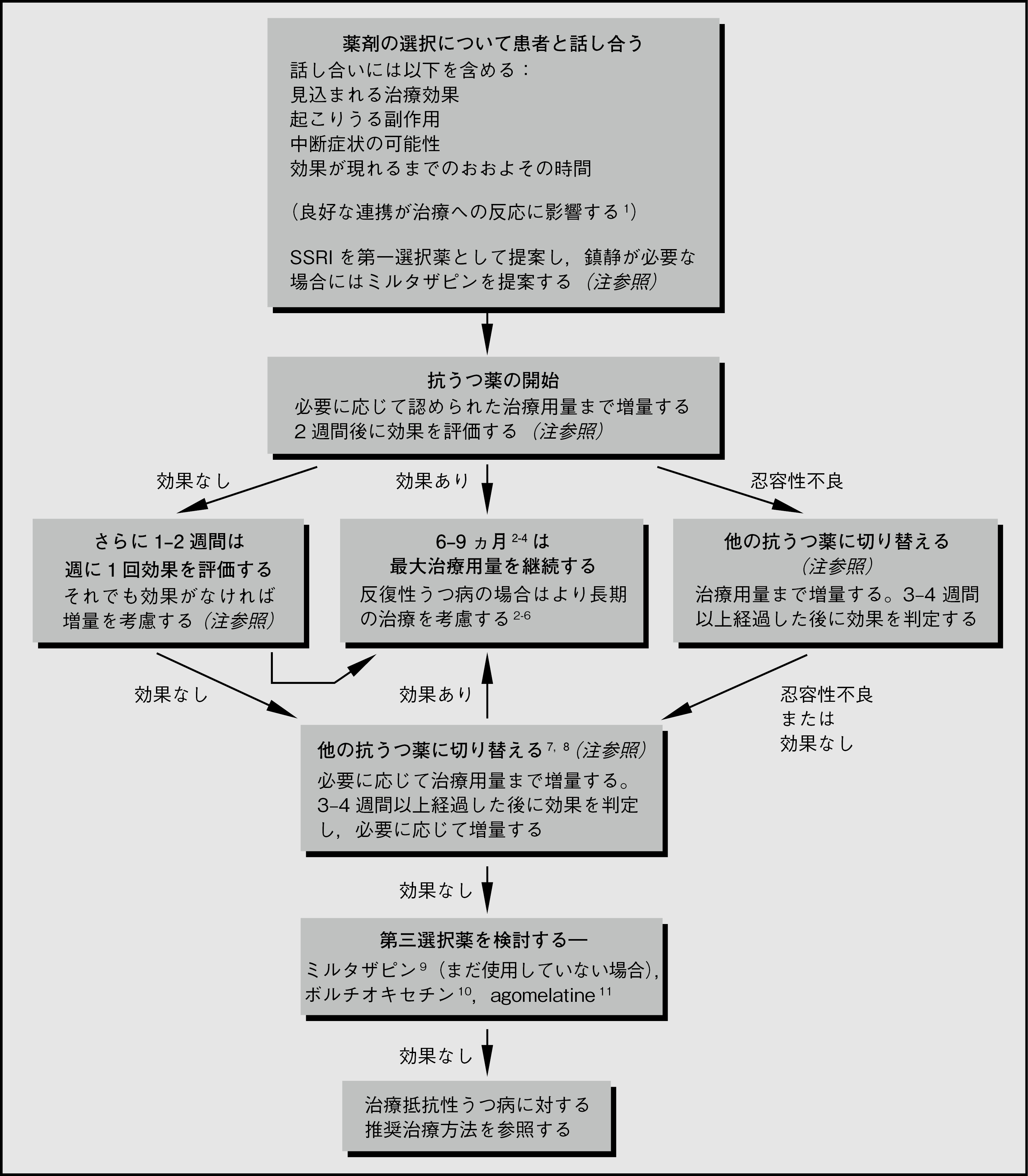

うつ病の薬物療法を図3.1にまとめた。

図3.1 うつ病の薬物療法

注

- 薬剤の効果を評価する試験では,モンゴメリ・アスベルグうつ病評価尺度(MADRS)12やハミルトンうつ病評価尺度(HDRS)13等の評価法が用いられる。HDRSは現在ではやや時代遅れで,MADRSに精通している臨床医は非常に少ない(しかしMADRSは重症度および症状の変化を測定する尺度として最良であると考えられる)。Patient Health Questionnaire-9(PHQ-9)14は簡便であり,うつ病の症状の変化の評価に推奨される(ただし,この評価尺度では症状の重症度よりも頻度を重視している)。

- 抗うつ薬の選択は患者と臨床医の好みに大きく左右されるが,SSRIか,鎮静が必要な場合はミルタザピンを推奨する専門家がほとんどである。最大規模のネットワークメタ解析15で,ノルアドレナリンとセロトニン双方の取り込みに作用する薬剤が最も有効である(特に評価の高い6剤のうち5剤が二重作用を有する抗うつ薬である)が,agomelatineおよびSSRIは治療中断率が最も低いことが示唆されている。新規抗うつ薬を検討した2018年のネットワークメタ解析16では,levomilnacipran,vilazodoneおよびボルチオキセチンの従来型薬剤に対する明らかな優位性は,認められたとしてもわずかであることが示唆された。

- 2週間後の評価は,最終的な転帰を判定するうえである程度有用である17。2週間後に症状スコアにおける改善の許容された閾値に到達していない患者で,最終的に効果が認められるのは約30%のみである。2週間後に全く改善がみられない,または悪化している場合,その後効果が得られる患者はさらに少ない。

- 忍容性が低い場合に,抗うつ薬の薬剤クラスを変更することが一部の研究で支持されており18,理論的には強力な根拠がある。臨床では,あるSSRIに対して忍容性がなくても他のSSRIに忍容性を示す患者は多い。

- 反応がみられない場合,同一クラス内での薬剤切り替えが有効であるとするエビデンスがいくつかあるが8, 19-22,臨床でよく行われているのは他のクラスの薬剤への切り替えであり,この方法はいくつかの解析で支持されている23。米国精神医学会(APA)は,いずれの選択肢も推奨している2。2018 NICEガイドラインの草稿24では,抗うつ薬間の切り替えを支持する説得力のあるエビデンスはほとんどなく(別の解析でも同様の結果25),この段階では抗うつ薬の併用あるいは第二世代抗精神病薬(SGA)の追加という選択の方がよいと示唆されている。ある治療が失敗した場合の切り替えを支持する最も有力なエビデンスが得られているのは,おそらくボルチオキセチンである10。

- 大部分のSSRIにおいて増量がうつ病に推奨されるというエビデンスは,少なくとも重症度を総合的な評価尺度スコアで評価した場合には,ほとんどない26。HAMDにおける気分のパラメータのみを検討した場合には,SSRIに用量反応関係が示唆される27。ベンラファキシン,エスシタロプラム,三環系抗うつ薬の増量は有効であるかもしれないと示唆するエビデンスがある3。一般に,増量によって有効性が増加する程度は小さい(SSRI,ベンラファキシン)ないしは増加することはない(例:30mg/日を超えるミルタザピン)一方で,忍容性に関しては確実かつ明らかに有害な影響を及ぼす28。

- 副作用に対して忍容性がない場合,もしくは3-4週間以内に全く効果がみられない場合は早期(例:1-2 週間後)に切り替える。薬剤の変更時期に関する意見は様々であるが,抗うつ薬は比較的早期に効果が現れるので29-31,2-6週間経過しても無反応であれば,その後も無反応であることが予測される32-34。3-4週間経過しても全く改善がみられない場合は,治療を変更すべきである[英国精神病理学会(BAP)のガイドラインでは4週間を提案している3]。この時点でいくらか改善があった場合には,さらに2-3週間治療を継続して評価する(本Chapterの「抗うつ薬─概論」の項を参照)。

(桐野 創)

参照文献

- Leuchter AF, et al. Role of pill-taking, expectation and therapeutic alliance in the placebo response in clinical trials for major depression. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 205:443-449.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Third Edition. Washington, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- Anderson IM, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacology 2008; 22:343-396.

- Crismon ML, et al. The Texas medication algorithm project: report of the Texas consensus conference panel on medication treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:142-156.

- Kocsis JH, et al. Maintenance therapy for chronic depression. A controlled clinical trial of desipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:769-774.

- Dekker J, et al. The use of antidepressants after recovery from depression. Eur J Psychiatry 2000; 14:207-212.

- Nelson JC. Treatment of antidepressant nonresponders: augmentation or switch? J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59 Suppl 15:35-41.

- Joffe RT. Substitution therapy in patients with major depression. CNS Drugs 1999; 11:175-180.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. Clinical Guidance [CG90]. 2009 (reviewed December 2013); http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/cg90 .

- Montgomery SA, et al. A randomised, double-blind study in adults with major depressive disorder with an inadequate response to a single course of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor treatment switched to vortioxetine or agomelatine. Human Psychopharmacology 2014; 29:470-482.

- Sparshatt A, et al. A naturalistic evaluation and audit database of agomelatine: clinical outcome at 12 weeks. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013; 128:203-211.

- Montgomery SA, et al. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382-389.

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296.

- Kroenke K, et al. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16:606-613.

- Cipriani A, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 391:1357-1366.

- Wagner G, et al. Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran, vilazodone and vortioxetine compared with other second-generation antidepressants for major depressive disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2018; 228:1-12.

- de Vries YA, et al. Predicting antidepressant response by monitoring early improvement of individual symptoms of depression: individual patient data meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2019; 214:4-10.

- Köhler-Forsberg O, et al. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2019; 139:404-419.

- Thase ME, et al. Citalopram treatment of fluoxetine nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:683-687.

- Rush AJ, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1231-1242.

- Ruhe HG, et al. Switching antidepressants after a first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:1836-1855.

- Brent D, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 299:901-913.

- Papakostas GI, et al. Treatment of SSRI-resistant depression: a meta-analysis comparing within- versus across-class switches. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63:699-704.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: treatment and management - Full guideline (Draft for Consultation). 2017; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/GID-CGWAVE0725/documents/draft-guideline .

- Bschor T, et al. Switching the antidepressant after nonresponse in adults with major depression: a systematic literature search and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2018; 79.

- Adli M, et al. Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 255:387-400.

- Hieronymus F, et al. A mega-analysis of fixed-dose trials reveals dose-dependency and a rapid onset of action for the antidepressant effect of three selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Trans Psychiatry 2016; 6:e834.

- Furukawa TA, et al. Optimal dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine in major depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6:601-609.

- Papakostas GI, et al. A meta-analysis of early sustained response rates between antidepressants and placebo for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26:56-60.

- Taylor MJ, et al. Early onset of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant action: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1217-1223.

- Posternak MA, et al. Is there a delay in the antidepressant effect? A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:148-158.

- Szegedi A, et al. Early improvement in the first 2 weeks as a predictor of treatment outcome in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis including 6562 patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:344-353.

- Baldwin DS, et al. How long should a trial of escitalopram treatment be in patients with major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder or social anxiety disorder? An exploration of the randomised controlled trial database. Human Psychopharmacology 2009; 24:269-275.

- Nierenberg AA, et al. Early nonresponse to fluoxetine as a predictor of poor 8-week outcome. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1500-1503.